Mierle Laderman Ukeles, care work, time impoverishment & Sustaining Your Life as an Artist

"In such erasure lies joy." —Doireann Ní Ghríofa

Certain artists’ lives and work recur in writing by women approaching or in the thick of motherhood. Paula Modersohn-Becker, Louise Bourgeois, Alice Neel, Mierle Laderman Ukeles. I approach these subjects with trepidation. Why must I, too, amble down such well-trodden territory?

My answers to myself are thus:

To some these names are new / There’s no “new” subject matter under the sun / The only newness in writing is in how not what / My task writing is to tell a story from my mind, to show how I think, to show something new to myself along the way

I had planned not to write anything new this month. It was my birthday month, and tax season, and I felt unsure of what and whom to write about. I planned to publish a previously written essay not yet available online on one of those names above.

And then something happened.

Another task of writing: Write about the day unlike all the other days.

One day, in the clarity of fury, Mierle Laderman Ukeles (who is still very much alive) sat and wrote, in one session, her “Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!”:

“I am an artist. I am a woman. I am a wife. I am a mother (random order).

I do a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc. Also, (up to now separately) I ‘do’ Art.

Now, I will simply do these maintenance everyday things, and flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them as Art.”

After the birth of her first child, Ukeles’s lively and engaging life as an artist evaporated. “People stopped asking me questions, stopped thinking of me as anything other than a mother,” she told the New York Times in 2016. “I was in a crisis because I had worked years to be an artist, and I didn’t want to be two people. It seemed like I could be an artist only by being two people.”

In the manifesto, Ukeles situated maintenance in opposition to progress and innovation. Art (and broader American culture) prizes the individual, the new; change, development, excitement, advance. Part of maintenance’s duty is to prop up prestigious progress:

“keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance; renew the excitement; repeat the flight.”

Avant-garde art and conceptual art, she argued, claimed “pure development and change,” yet are made of maintenance ideas and materials and employ maintenance processes.

“The sour ball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?”

Maintenance, at its best, disappears. Maintenance is visible only when it fails: no gas, no milk, no clean underwear. A rupture in the flow. Maintenance doesn’t earn praise or appreciation; it tends only to invite criticism.

“Maintenance is a drag,” Ukeles wrote, “it takes all the fucking time.”

But maintenance is also a function of the Life Instinct, she wrote: unification, endurance of systems and civilizations, equilibrium. Maintenance was unsung but essential, expected for low wages or no pay at all. Here, Ukeles saw creative possibility.

Patricia C. Phillips in Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Maintenance Art:

“[T]he idea that people are diminished by recurring, repetitious work is a prevalent and often unquestioned one. In Manifesto for Maintenance Art Ukeles proposed instead that enormous potential for creativity lay in the willingness to accept and understand the broad social, political, and aesthetic implications of maintaining.”

Ukeles described an exhibit in which she would wax floors, dust, and wash walls, “i.e. floor paintings, dust works, soap sculpture, wall paintings.”

“The exbibition area might look ‘empty’ of art, but it will be maintained in full public view.”

SUSTAIN verb 1: to give support or relief to 2: to supply with sustenance : NOURISH 3: KEEP UP, PROLONG 4: to support the weight of : PROP also : to carry or withstand (a weight or pressure) 5: to buoy up sustained by hope 6a: to bear up under 6b: SUFFER, UNDERGO sustained heavy losses 7a: to support as true 7b: to allow or admit as valid 8: confirm SUSTAIN noun : a musical effect that prolongs a note's resonance

I am taking a class with the writer, choreographer, artist-career-development sage Andrew Simonet called “Sustaining Your Life as an Artist.” The class builds on his practical and inspiring book, Making Your Life as an Artist.

As I think about Mierle’s positioning of advancement and maintenance, I think of Andrew’s take on career and mission, and how to re-imagine old ways of capitalistic, patriarchal thinking:

Andrew gives us homework each week. Then he invites us to meet in breakout sessions. He is generous with his time, in the manner of someone who has organized his life to allow for that without resentment or overextension.

This is what happened that changed everything. This is the event that urged me to sit down and write this month’s newsletter to you.

Andrew asked us to record how we spend our time. A time diary, a log, an accounting of hours spent.

This is an assignment I had previously read in his book and ignored; I didn’t have time for it. (Obviously.)

A familiar scene in our house: M returns from an errand begun after dropping off our child at daycare, one that boomeranged, then ballooned. He wolfs a peanut butter sandwich and returns to the driver’s seat to pick up our kid. What a waste of a day, he says.

An aspiration reappears throughout my diary over the last two years: 10 hours of writing time a week. It is difficult for me to even write it here, publicly, for the shame of how modest and rarely achieved such a goal seems for a professional writer.

That shame, I discovered, is precisely why I had never accounted for my time when previously given the homework. The assignment felt like an accusation-in-waiting, a setup for a gotcha. If I saw how I was spending my time, I would know that my inability to find ten hours a week to write is a personal and moral failure to align my values with my actions. That failure is a demonstration of my lack of commitment to my art. The problem, I would find, is me. I couldn’t sustain the blow.

Who knows where the time goes? I do now. I did the homework. Andrew’s homework, Mierle’s work.

make toast pack lunch wash dress buckle car seat unbuckle car seat grocery shop chop sauté stir put away wipe counters wipe bottoms scrub potties load dishwasher empty dishwasher eat something drive park gas-up exercise teeth brushing bedtime bath time deposit checks fill out paperwork mail package invoice clients file story file papers respond to mail return email respond to text write buy birthday present buy wrapping paper wrap present get pink eye pick up prescription administer antibiotics miss birthday party water tomatoes apricot tree monstera stag horn fern begonia plants we’ve forgotten the names to drop off birthday gift the day after party etcetera

With 24 hours a day, why can’t I meditate, write a novel, train for a half-marathon, raise my child, make money, pay the mortgage, all at the same time now? Now I knew. It was one the most validating reality checks of my life.

Maintenance work disappears, but the time diary forced my attention to how much I “do” each day even when I don’t “do Art.” The exercise allowed me to see the value and importance in all the necessary tasks of a “wasted day.” I could also recognize the artfulness of my care work, particularly the playful, spontaneous improvisations, when I feel loose and alive, that are some of my favorite parenting moments.

Ukeles quotes a Balinese saying: “We have no Art, we try to do everything well.”

As a resource, time is a funny one. Each living day, we are all granted the same allotment. Individual and systemic realities force its allocation in different measure. Yet there is a very rich woman who has built a literary empire around the idea of not having enough time. She is time impoverished. When she interviews authors, she asks, “What don’t you have time for?” I have heard people answer with what they’d like to do but don’t. They are talking about regret and sorrow. I hear the question in the inverse. I don’t have time to click the link you sent me. I don’t have time to sew on my own button. I am answering the question: What don’t you care about? Another question is, What do you?

I could see, from the way I spent my time, that I cared about making good, wholesome food. I cared about keeping my child well. I cared about keeping the plants alive and living comfortably somewhere between relative tidiness and filth. And I cared, care deeply, about keeping my writing life alive within and among the many other values of my life.

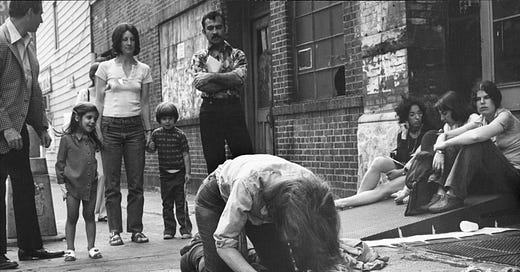

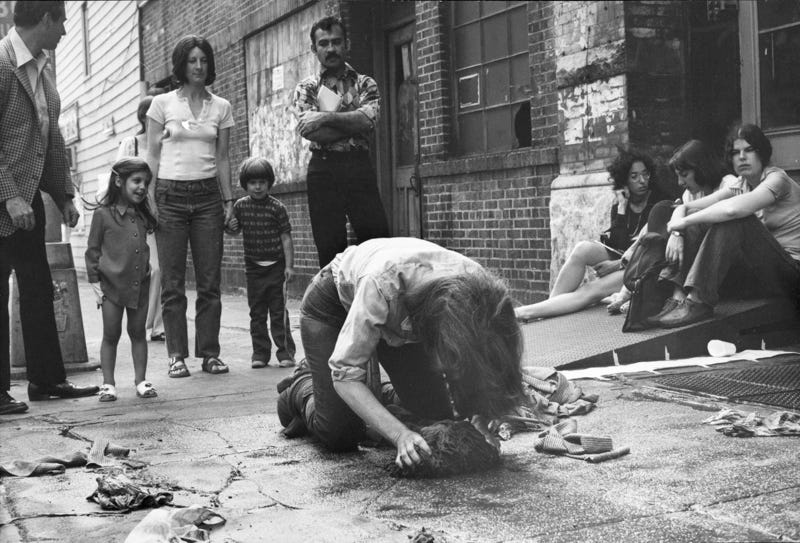

In 1973, Laderman Ukeles performed the invisible tasks of often private maintenance work at the Wadsworth Athaneum in Hartford, Connecticut.

Newspapers poked fun. Hey, if the cash-strapped Department of Sanitation could pitch its operation as conceptual art, they could snag a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Ukeles liked the idea, spoke to the Department of Sanitation commissioner, and scored the NEA grant.

Since 1977, Ukeles has held the unsalaried position of the New York Sanitation Department’s artist in residence. Over the last fifty years, she has devoted her art to maintenance work. In Touch Sanitation Performance, Ukeles spent 11 months walking every garbage collection route in New York and shook hands with 8,500 sanitation workers. To each one she said, “Thank you for keeping New York City alive!”

“The real art work is the handshake itself,” Ukeles said.

relationships = maintenance

Ukeles sat on the curb with her colleagues, often denied service at restaurants, to eat lunch and kvetch.

“It’s like I AM the garbage,” one sanitation worker told her, “or the garbage is my fault.”

Flush them up to consciousness

an enduringly brilliant line

What will you flush up to consciousness today?

Procrastination is not a character flaw, Andrew says. It’s a design problem.

If you find yourself avoiding something, the task is not small enough yet. Finish novel is not a task. Nor, for me, is write for 10 hours a week. Or write 1,000 words.

Dream bigger, he says. But plan much, much smaller.

Open my novel document. Sit with it for five minutes. Approach my own work-in-progress with friendliness, curiosity, and play.

If relationships = maintenance, then I want my relationship with my work to be a positive, sustaining one like Sheila Heti described in Motherhood:

“I had such a nice time the next day, pacing in the sunlight before my 4:30 lecture realizing how much writing has given me, and feeling so lucky that this passion was mine — right there in the center of my life. And you're never lonely while writing, I thought, it's impossible to be — categorically impossible — because writing is a relationship. You’re in a relationship with some force that is more mysterious than yourself. As for me, I suppose it has been the central relationship of my life.”

Add Ukeles to an inspirational post-it wall:

“Everything I say is Art is Art.”