Vanessa Bell, disincentives, Patti Smith & domestic liberation

“The domestic strain in you is very odd. How do you account for it? Perhaps it’s the sign of real genius. If you were only very clever you wouldn’t care for such things.” -V. Bell to V. Woolf

Thinking with artists about the project of making work whilst living life is of never-ending fascination to me. Find out more about my work, including mentorships and old-fashioned manuscript consultations. I’d love to hear from you.

“The truth is,” writes Claire Dederer in Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma:

“art-making and parenthood act very efficiently as disincentives to one another, and people who say otherwise are deluded, or childless, or men.”

I have thought of this line many times since I read it. Perplexed, I have discussed it with other writers with children. Within this paradigm, I conclude I must be deluded.

Perhaps I misunderstand the word disincentive?

A deterrent, Merriam-Webster says. (Deterrent: serving to discourage, prevent, or inhibit.) Cambridge Dictionary calls a disincentive something that makes people not want to do something or not work hard. The OED adds a source of discouragement, especially to economic progress or development.

Certainly, no one’s getting rich from having children, with that much I agree. Yet I return to the advice of a Swedish poet I met at residency. Sometimes you’re playing with blocks, she said. Sometimes you’re writing a poem. The two flow into each other.

Who says I am not writing a poem as I place this rectangle atop that one?

What is more incentivizing to a pregnant artist than a due date?

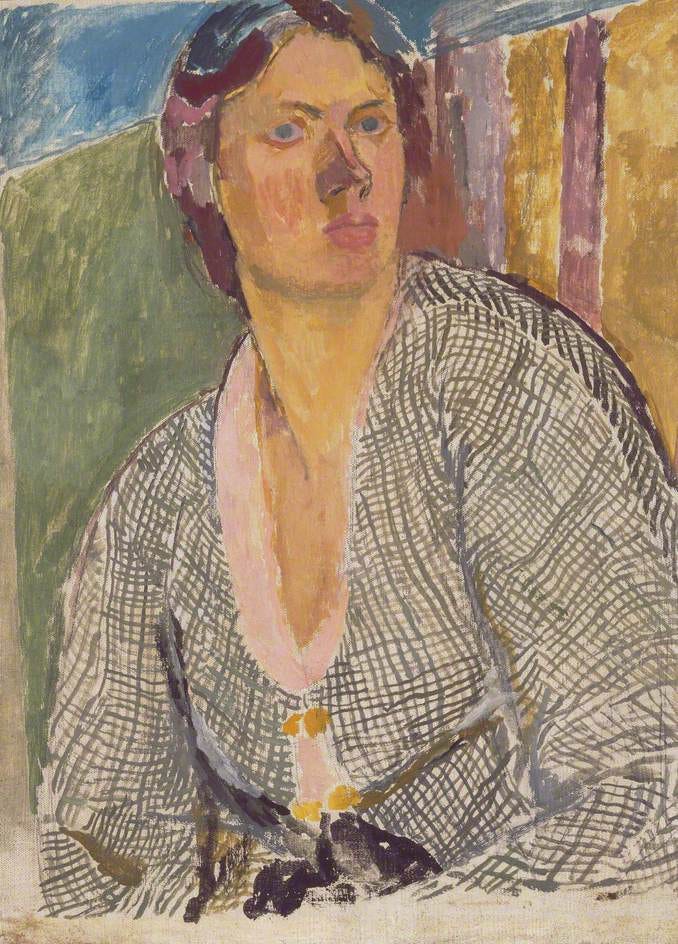

The whereabouts of The Nursery (1930-2) are unknown, likely destroyed when Vanessa Bell’s studio was wrecked in a London bombing during World War II. I find a small black-and-white photograph of the large-scale work in Frances Spalding’s biography of Bell. She is best known as Virginia Woolf’s sister, but Vanessa Bell, among the first British artists to embrace pure abstraction, eschewed her Victorian upbringing and remade her life as a radical in private life and on the canvas.

Picture a monumental canvas. There’s a scattering of toys on the floor before a fireplace: sailboat, toy trumpet, horse figurine, spinning top, splayed book. A nanny sits on a sofa holding a naked toddler, who twists from her grasp. The mother, seated on a low ottoman, observes an older child, perhaps four, also nude, his back toward the viewer. He is all round bottom and soft contrapposto stance, his gaze lowered to the string in his hand which leads back to the model horse. The women watch the children, the children look elsewhere.

Spalding called the picture “a nostalgic evocation of motherhood” but nostalgia summons a one-note flavor, and this picture is a complex one; within this scene of domestic intimacy individuation begins: “While celebrating motherhood, the painting is also poignantly about loss,” Spalding writes.

When Vanessa wrote to Virginia after reading The Waves, it was the problem of this painting she needed to discuss:

“I have been for the last days completely submerged in The Waves and am left rather gasping, out of breath choking half drowned as you might expect. I must read it again when I may hope to float more quietly, but meanwhile I’m so overcome by the beauty…it’s impossible not tell you or give you some hint of what’s been happening to me. For it’s quite as real an experience as having a baby or anything else, being moved as you have succeeded in moving me…

Will it seem to you absurd and conceited or will you understand at all what I mean if I tell you that I’ve been working hard lately at an absurd great picture I’ve been painting off and on the last 2 years—and if I could only do what I want to—but I can’t—it seems to me it would have some sort of analogous meaning to what you’ve done. How can one explain, but to me painting a floor covered with toys and keeping them all in relation to each other and the figures and the space of the floor and the light on it means something of the same sort that you seem to me to mean.”

Woolf’s reply: “I always feel I’m writing more for you than for anybody.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LOST ART to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.