Anni Albers, thread, self-publishing, making magic of what we find on earth

"I have this very what you call today 'square' idea that art is something that makes you breathe with a different kind of happiness." —Anni Albers, 1968

Imagine it’s a golden winter afternoon, fading light filtered through brittle ochre leaves, it’s basically a Terrence Malick film, and you are early to an exercise class. Imagine it is not long after your child’s fourth birthday and not long before he tells you he is sad because everything is changing. Christmas is over, the recycling brims with wine bottles. At night, somewhere beyond your small fenced backyard, owls hoot to one another in the dark. There are only six minutes or so before you must lift heavy weights, but you’re not about to spend all that time foam rolling. So you read Anni Albers, “Material as Metaphor”:

“A short while ago I had a visit from 10-week old baby who looked at me wide eyed and I thought somewhat puzzled and was struggling as if trying to tell me something and did not know how.

And I thought how often did I feel like that, not knowing how to get out what wanted to be said.

Most of our lives we live closed up in ourselves, with a longing not to be alone, to include others in that life that is invisible and intangible.

To make it visible and tangible, we need light and material, any material. And any material can take on the burden of what had been brewing in our consciousness or sub-consciousness, in our awareness or in our dreams.”

You don’t need to imagine the tears, fat and sodden as Santa Claus after his midnight ride. The interior of the car is gray leather and plastic, and the surrounding world tugs with its precious, mundane materiality: droopy lycra, the scrabble of weeds outside city hall, the woman ceremoniously riding a bicycle, a large Frida Kahlo-flower where a helmet should be.

“Any material,” Anni says.

During class, a girl crochets pink and gray friendship bracelets for everyone while she waits for her mother. Did you get one? she asks me. She’s wearing a pink and orange tie-dye sweatsuit and tells me her name is Ella. She ties a tight bow around my wrist. That night, my son asks if he can wear the bracelet to school, so I tie it on his wrist, but it’s so big it slides off before he’s out the door.

How do we choose our specific material, our means of communication? “Accidentally,” says Anni.

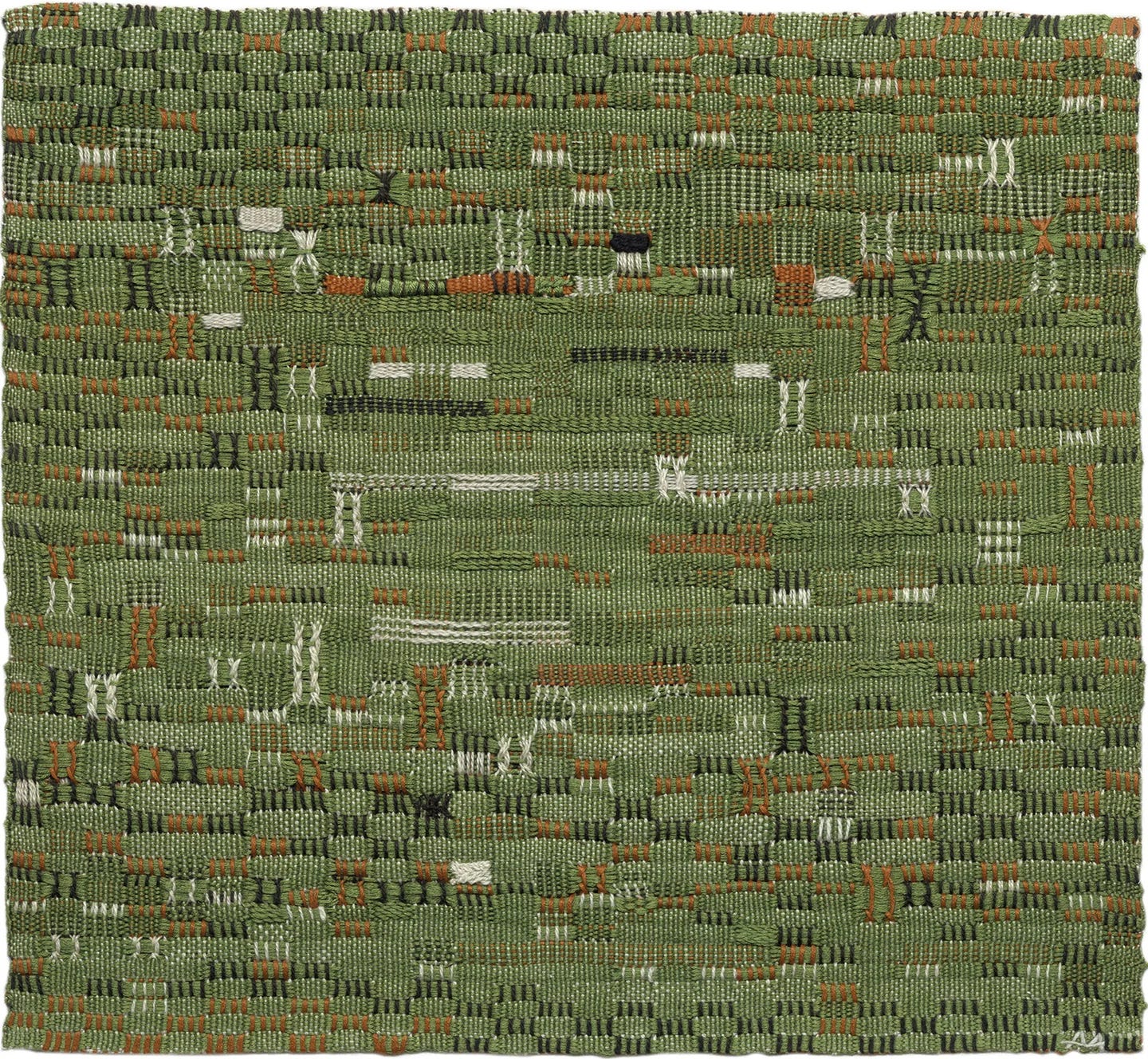

Our materials today are words and daily life and thread. In 1922, threads ensnared Anni Albers against her will. Assigned to weaving at the Bauhaus because she was a woman, Anni thought it was “sissy stuff.” Painting, though, was too free. The loom’s confining grid of warp and weft focused her attention.

“I felt that the limitations and the discipline of the craft gave me this kind of like a railing. I had to work within a certain possibility, possibly break through, you know.”1

In 1933, Nazis padlocked the Bauhaus and Anni and her husband were ready to leave Germany. Josef was invited to teach at the newly formed experimental Black Mountain College, where Anni established the weaving workshop in 1934. The Albers traveled extensively, driving from North Carolina to Mexico and returning two dozen times over the next forty years. In Argentina, Chile, and Peru, Anni became a scholar of South American weaving traditions. “Art is everywhere!” they exclaimed joyously.

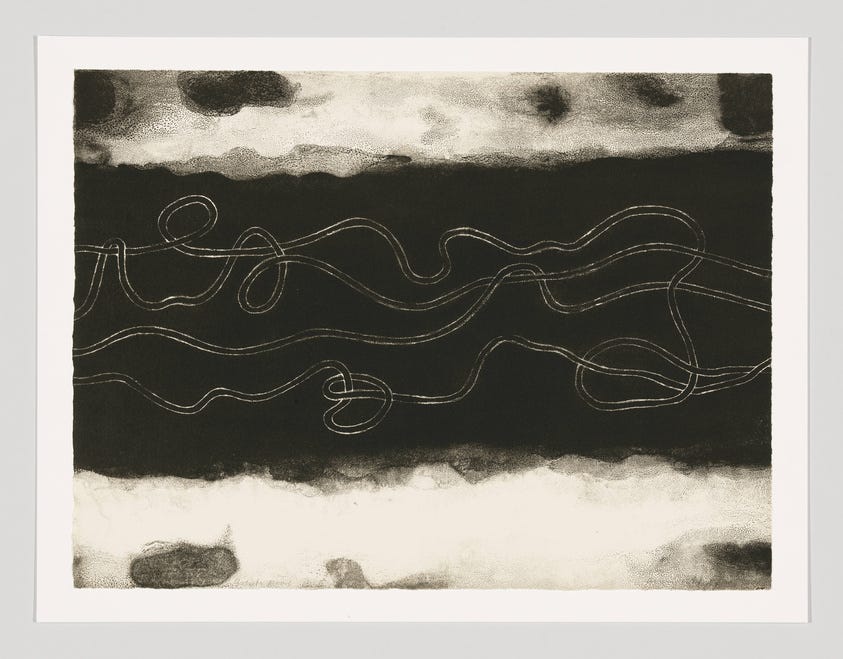

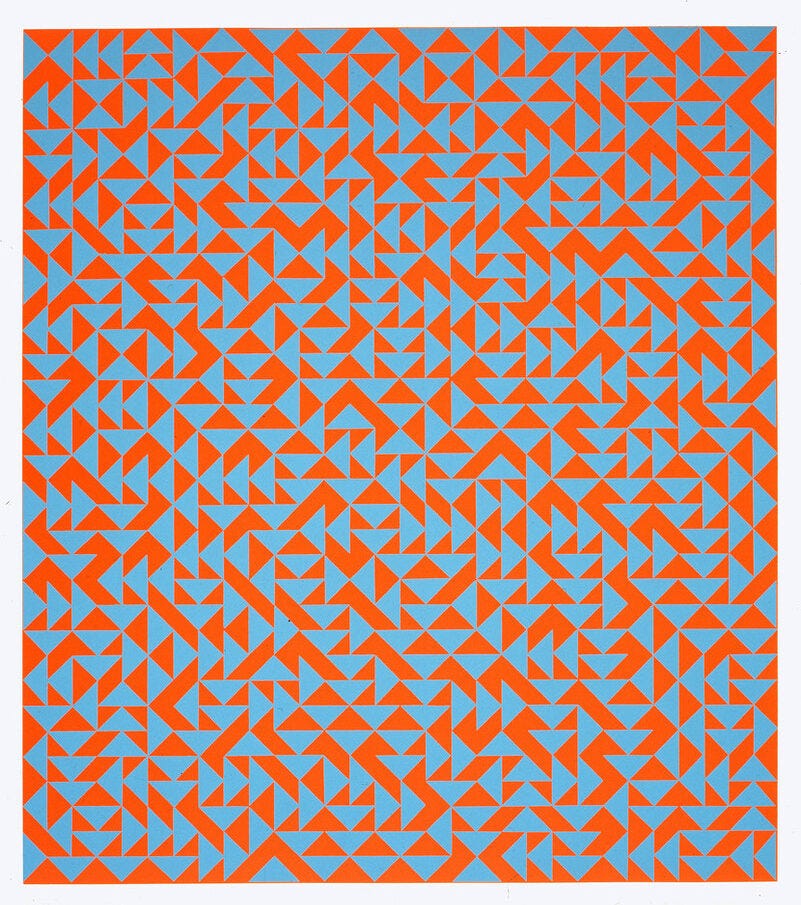

In 1949, the Museum of Modern Art mounted its first solo show of a textile artist on Anni Albers. She loved innovation, wove cellophane into fabric for sound-absorption, designed carpets and fabric room dividers, as well as making what she called “pictorial weavings,” abstractions to hang on the wall. She wrote two books of theory, On Designing in 1959 and On Weaving in 1965. In the mid-’60s, when she tired of the loom’s guardrails, Albers learned printmaking. She was in her 60s. Along with artists such as Ruth Asawa and Louise Nevelson, Anni had a two-month residency at Los Angeles’s famed Tamarind Lithography Workshop where she made her Line Involvements series.

Anni wrote:

“The one great worrying question in a student’s mind is this: where do I go from here? And my answer has always been, you can go anywhere from anywhere.”2

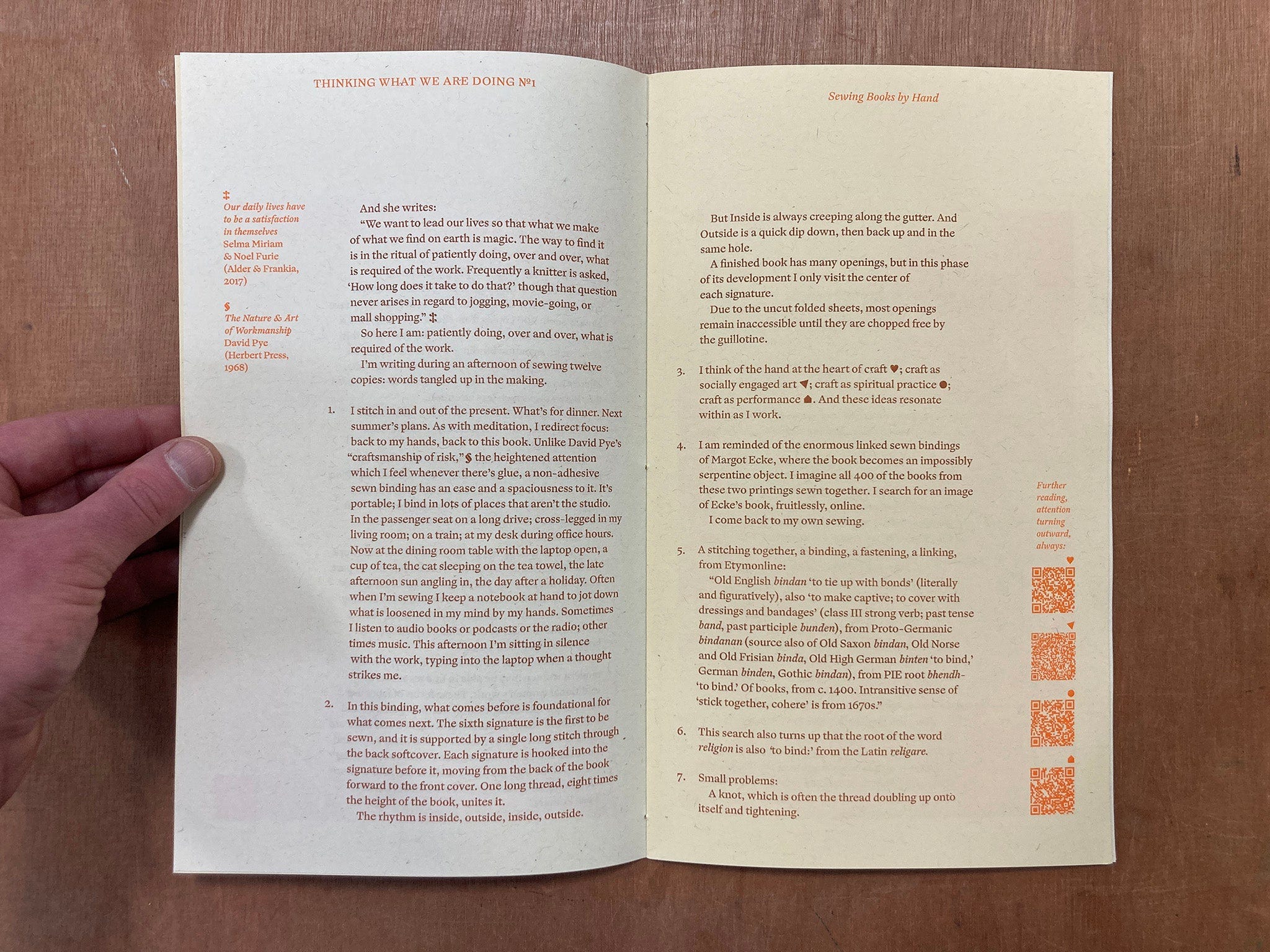

Sewing Books by Hand is not a manual on sewing books by hand; it is about thoughts that arise as one sews books by hand. In particular, the thoughts that arose as artist Emily Larned sewed Our daily lives have to be a satisfaction in themselves, an archival history of the Connecticut feminist restaurant and bookstore, Bloodroot.

The book is more beautiful than any online images indicate. (We must imagine the same is true for Anni’s work pixelated before us, that the same is true for most things.) The materials draw me close. The binding is sewn with golden thread, fine as angel hair. Brown typeface, orange images of 19th century women bookbinders, all printed Riso on French paper. It’s haptic seduction, a word I learn from the book itself: “Haptic from the Greek haptikos: ‘touching;’ but also ‘to grasp,’ ‘to perceive.’”

“The task for today is paying attention,” Larned writes. She’s sewn this same multi-signature binding hundreds of time before, the process is in her fingers, and her thoughts can drift beyond the gold thread to dinner, summer plans. Larned quotes India Johnson’s essay “A Century of Craft”:

“Intensive craft training can provide us with the ability to articulate the workings of embodied cognition. It allows us to assert, from authority of our own experiences, that how things are made matters—that meaning does not exist separately from the means of production.”

Sewing Books by Hand tracks thoughts like a fox through the snow. Larned writes:

“I’m writing during an afternoon of sewing twelve copies: words tangled up in the making.”

There is so much to say about the material of publishing itself, discoveries that have surprised me in the past year as I mailed out the first print edition of this newsletter to paid subscribers. This quote from Thomas A. Clark of Moschatel Press in Sewing Books by Hand is pertinent to my discoveries and to anyone publishing on Substack, on a blog, in zines, or in any self-determined fashion:

“Self-publishing can constitute not a vanity, but a freedom…the means can become creative. Everything can be exact but also light, since production is a way of life, an activity rather than an occasion.”

In my life, I want every material to matter. This book sewn by hand, this bracelet woven by a girl I just met, her hair uncombed from sleep, vegetables grown in a field so close I could fly a paper plane into it. The lives of objects reverberate; I’m this-close to saying “high vibrations,” but I can stop myself. What if there is always a haptic knowing — always sensed though not always articulated — either energetically elevating or dragging us down? I think of this when I enter my favorite shop, each wooden spoon alive as a tree. Then earlier this week, I was duped. My son came home from school wearing another child’s sweatshirt. Its softness seduced me, I was enchanted by its peacock blue. Amazon Basics, the tag read. I felt weirdly betrayed, but by whom or what? My senses? Another parent’s sartorial choices?

“Usefulness does not prevent a thing, anything, from being art,” Anni Albers wrote in On Weaving:

“It is the thoughtfulness, care, and sensitivity in regard to form that makes a house or a fabric turn into art and it is this degree of thoughtfulness, care, and sensitivity that we should try to achieve.”

On Weaving, Albers wrote, was “not a guide for weavers or would-be weavers.” Rather, she hoped to “include in my audience not only weavers but also those whose work in other fields encompasses textile problems.”

Who among us does not have a textile problem or at least a material one? Run your fingers along the surface of the day. Everything matters, our attention is limited, and I’m greedy for meaning. I want everything to be good and true: the song on the radio, the novel on the bedside, my eggs. Truth is enough. I had a teacher who said not every sentence in a “nonfiction” work had to be true, but the writer had to know if it was—that’s truth with oneself. M.F.K. Fisher often wrote of honest food. And from truth, it’s an easy Keats-hop to beauty; I think frequently of what Betty Woodman said:

“I wanted to be a potter and make useful, functional objects that would change society. Because if you have beautiful things to use, it changes the kind of person you are.”

Depending on your mood, this may all sound rather precious and privileged and pretentious, a little too Alice Waters, a little too transcendence-in-a-slice-of-bread, too evil-in-a-sweatshirt.

Well.

To me, the great appeal is simplicity. If one has the ability, to have one’s values and aesthetics appear in one’s relationships and soup bowl, in one’s bank account and in one’s art. To have fewer, better choices. For it all to be in accordance.

We try at least. The truthful acknowledgement of the gap between vision and execution is the artist’s daily reckoning.

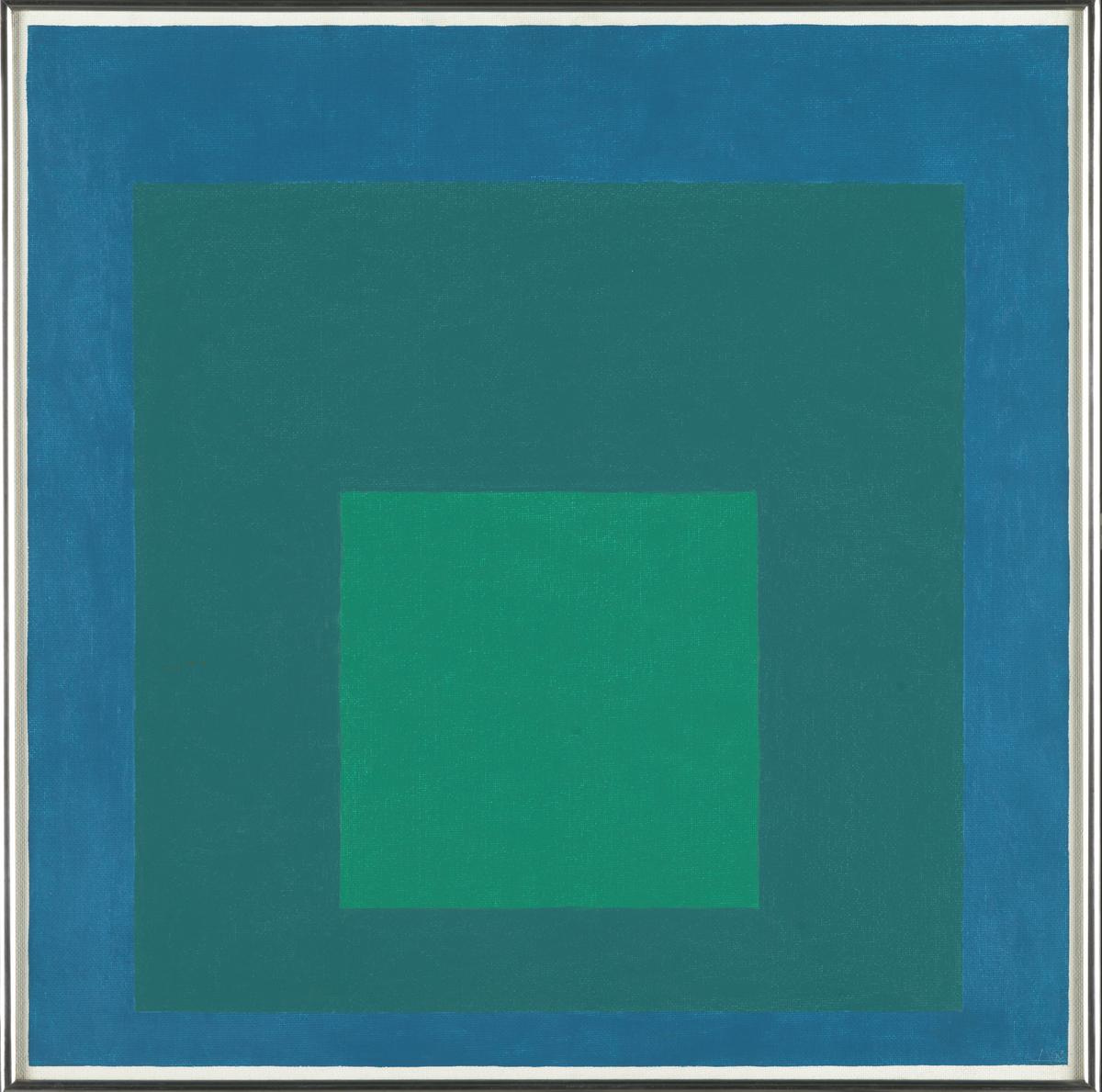

Josef had grown up poor, Anni had not, and the couple struggled most of their lives to earn enough money to live. Josef + Anni Albers: Designs for Living contains photos of the couple’s various homes. The bedrooms are starkly monastic. On the standard-issue white electric stove sits an original Chemex, given to Josef by designer and chemist Peter Schlumbohm. A child visiting the couple’s home noted the striking similarity between the living room’s square off-center air-conditioning vents and Josef’s Homages to the Square. When asked how he painted these pictures he said, “I paint the way I spread butter on pumpernickel.”

“The implication, of course,” Nicholas Fox Weber writes:

“was that to paint a good painting and cook a good dish are much the same. You take well-chosen ingredients, assemble them in correct quantities, and put them together systematically. Nothing fancy, please. And understand that a simple domestic activity—the following of a recipe, the spreading of butter on a piece of honest black bread, redolent of the earth, full of character and nourishment—is noble.”

Josef spoke at a design conference in the 1950s:

So I am looking forward To a new philosophy Addressed to all designers —in industry—in craft—in art— and showing anew that esthetics are ethics, that ethics are source and measure of esthetics.

When Emily mailed me Sewing Books by Hand, I asked her to send the book on Bloodroot, too, Our daily lives have to be a satisfaction in themselves by Selma Miriam and Noel Furie. The title reminded me of something my mother used to say about parenting, long before I needed such advice: There is no reward in the end, the reward must be in the day itself.

Emily Larned designed and edited the book, she writes in an introduction, because:

“many of us are starved for examples of how to live, everyday, in accordance with our values. We are searching for ways we can better sustain ourselves and our beliefs, and better support each other.”

In beautiful, timeless essays from the past forty years, Selma Miriam writes about how Bloodroot has ordered her life—around close relationships and hard work, books and knitting needles:

“We want to lead our lives so that what we make of what we find on earth is magic. The way to find it is in the ritual of patiently doing, over and over, what is required of the work.”

Patiently doing, over and over, what is required of our work, we grow increasingly intimate with our materials, be they beans or gold thread or lines on paper.

Anni wrote:

“The more subtly we are tuned to our medium, the more inventive our actions will become. […] The finer tuned we are to it, the closer we come to art.”

Making what we find on earth either art or magic: The more I write, the more I’m convinced they are the same thing.

https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-anni-albers-12134#transcript

Anni Albers, “Foreword.” The Woven and Graphic Art of Anni Albers. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985.