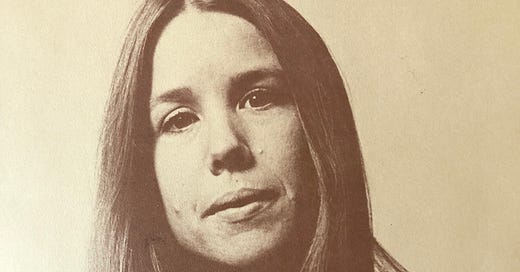

Kate Wolf, a love story

"The people I admire most are people whose lives are reflected in their work and their work is reflected into their lives, there is no separation." —Kate Wolf

I live in Northern California, a vast geographical area a small part of which some people call Kate Wolf country. In a manner of speaking, I live here because of Kate Wolf, which is another way of saying I live here because of love.

For fourteen years, I lived in Brooklyn, and most of that time in a quiet second-floor walkup in a neighborhood realtors called South Park Slope. I had moved there for my adult life, to be a writer in love. Eleven years into my tenure, two years after a divorce, my dear friend asked if I was up for a blind date. I was preoccupied with reorganizing around what I’d lost track of while in love, including writing and myself. I declined her offer.

Meanwhile, my prospective date was asked if he would like to be fixed-up. He also declined.

This is not how great love stories begin.

We met anyway, due to the trickery of our friends, at a Halloween party. Neither of us wore costumes. I had quit a big job for graduate school; he had quit a big job for what he wasn’t sure. I can see now what we had in common. We were both learning to say no.

Despite ourselves, we liked each other.

He’d holler up at my window from the sidewalk. There’s an incredible sunset! He asked me out for walks, on which I discovered a pocket in the rear of his coat for maps. I snaked my arm inside and pressed my palm to his low back, my hand a compass. We are here. The measure by which the map pocket charmed me cannot be overstated.

I balanced on his bicycle handlebars. The perilous ride was a perfect metaphor. I’ll never let a bad thing happen to you, he said, a well-intentioned lie from someone not yet ready to say I love you, too.

I was trying to learn a Kate Wolf song on guitar, “Across the Great Divide.” I’ve been walking in my sleep / countin’ troubles ‘stead of countin’ sheep. One night, I played the recorded version for this man who would not yet say I love you but who built me bookshelves and shoveled my car out of the snow. We sat on the back of the couch and listened silently. When the song ended, I was surprised.

Are you crying? I was crying, too, but then that was ordinary.

Kate Wolf always makes me cry, he said.

Then I was doubly surprised. Like every beloved discovery, I thought she belonged to me. He was a Northern Californian; he thought she belonged to him.

He owned all of her records, he said.

We were learning we might belong together, if only we could both stop saying no.

I've tried my best to understand Why we stand out here in the rain In our anger and our pain Afraid to feel the love that's in our hands

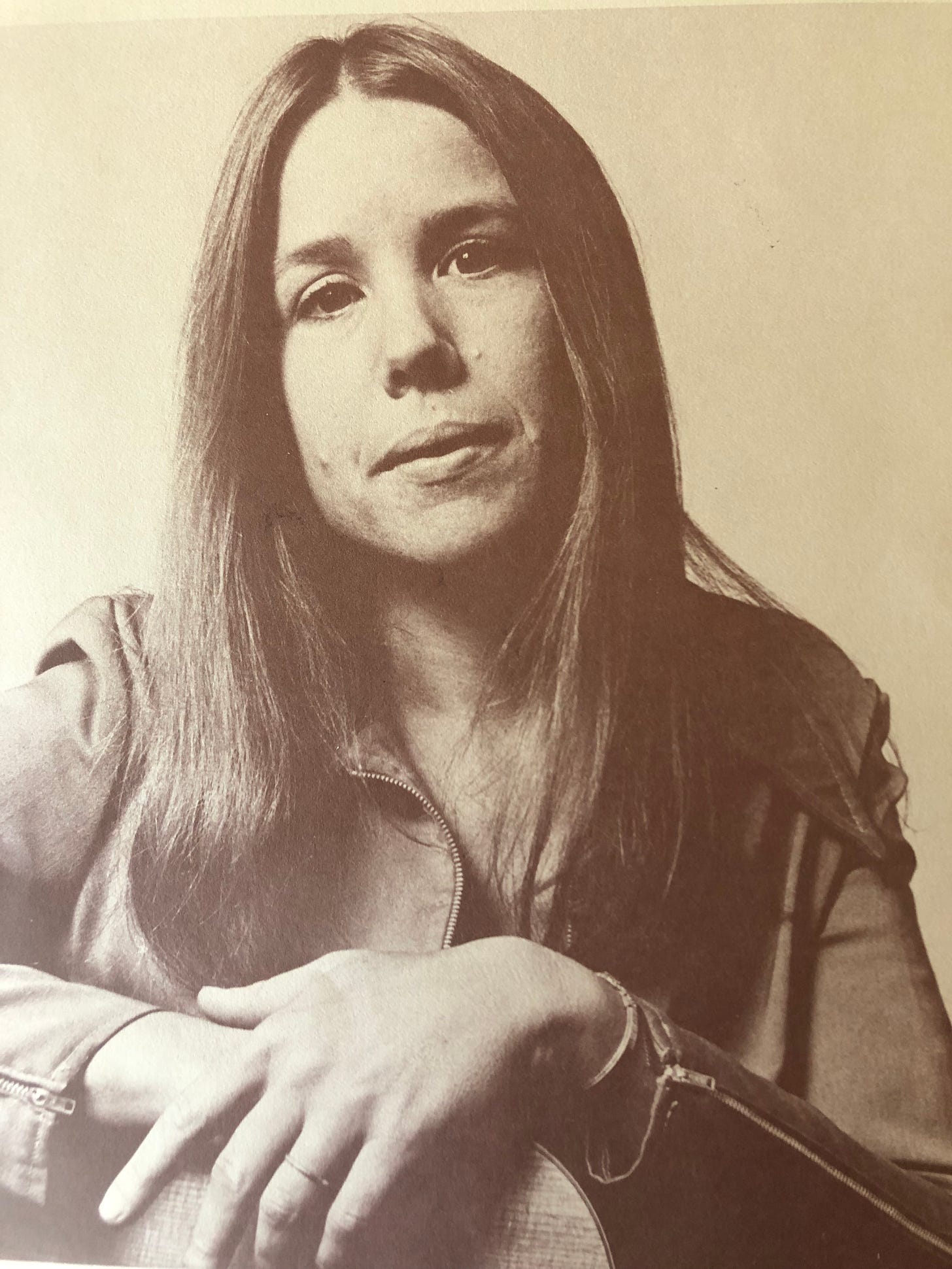

Kathryn Louise Allen was born January 27, 1942 in San Francisco.1 At age four, she began piano lessons with her grandmother and played into high school. She wanted to sing but mom said no. Then, self-conscious at sixteen, she gave up playing and performing. At nineteen, she met Saul (“That’s where I picked up the ‘Wolf,’ she said. “A good name is worth keeping”), fell in love, married, and had two children, Max and Hannah.

Kate Wolf called the 1960s — a decade she spent throwing dinner parties, sewing clothes, and baking bread — her numb period.

Breadcrumbs appeared. The babysitter arrived with a record of Rosalie Sorrels playing Utah Phillips. Enthralled, Kate sat down to learn the entire album.

“It’s amazing the little things people drop in your way,” she said.

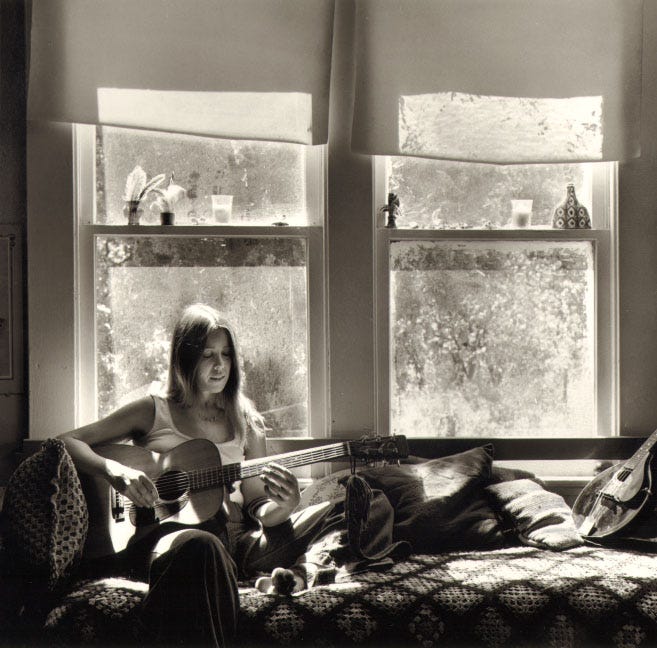

Through a long series of events involving friends of friends and broken down cars, Kate met folks in Big Sur who played music in their living rooms. They all became friends, and Kate began playing with them. They encouraged her.

Go out there and do it, they said.

“And I never had anybody say anything like that to me,” she said.

But she didn’t know how to write music.

Just sing your conversations, they said.

Feeling returned. In 1971, Kate parted ways with her husband (“I knew he didn’t want to be married to a musician,” she said. “He told me that,”). She moved to Sonoma County to pursue music, living in her ’57 Chevy for six months. The couple had joint custody, and Kate became a “weekend mother.”

“Women didn’t do that very much [in 1971]. I really understand single fathers. You hang out on weekends in the park and you try to find things to do when you don’t have a house.”

She found a job at the Sebastopol Times, performed once a week at a local bar, and soon, her children joined her. She got involved with their schools, and gigged twice a week in a little restaurant with avocado soup on the menu.

There was more living room singing. Kate’s songs blend elements of folk, traditional country, and bluegrass and “hold a sadness that’s like clear water in cupped hands,” a reviewer wrote in 1984. She sang about lilacs and apple orchards, chopping wood, bulletin boards outside country stores, greedy developers, and driving to the town dump. She sang about tequila and mending fences.

Kate’s band, The Wildwood Flower, played more benefits than Bob Hope, one writer quipped, and Kate hosted a two-hour Sunday radio show on Santa Rosa’s KVRE called Uncommon Country (later hosting the Sonoma County Singers Circle on KSRO). She organized folk festivals and met her idols.

She repeated this pattern: write, mother, work, sing; write, mother, work, sing.

“Magical things began to happen,” she said.

Kate’s story reminds me how simple the recipe for magic can be: Show up, get involved. Make your art. Introduce yourself. Support the local and artistic communities.

“How is an artist different than another person?” an interviewer asked:

“You never have any time off,” she said:

“You spend a lot of time observing, seeing, thinking about things. It’s your full life…I balk a little bit because I think all of us have artistry in us but I think to live a creative life, to live a life for creativity, is the source. You have to pay attention every waking and dreaming moment of your life. And it tends to affect everything….It's like living with your eyes and ears, your senses wide open all the time. That's why quiet is so important and that’s why it does affect your relationships. Sometimes you just need to go off by yourself or to ground yourself out in ways that aren’t always constructive. Once you get into the flow, where you’re in relationship to the world and people around you and yourself in a proper way, I think it’s really wonderful. It’s really nourishing, it’s an exciting way to be alive. But that’s what you learn. It takes a while.”

Back Roads by Kate Wolf and the Wildwood Flower was released in 1976 on Kate’s own label, Owl Records. Over five days in July, in a living room on the coast near Goat Rock, the album was recorded live on an old Langevin board and mixed live to a Re-Vox A77 reel-to-reel recorder. All the magic was in the moment.

Her second album, Lines on the Paper, came in 1977, also recorded and mixed live, this time in the bunkhouse at Chanslor Ranch near Bodega Bay. Kate had married band member, Don Coffin, and lived with her two children, two dogs, one cat, and nine chickens on three acres outside of Santa Rosa.

“We have something unique up here,” she said, “a kind of regional music all our own. We're different — not funky Berkeley or slick Los Angeles. We’re Sonoma County.”

The voice, that sad, sonorous voice. Why had her mother said no?

Kate Wolf’s voice is a hand-turned wooden bowl: deep, round, and full. To me, the beauty of her songs lives in their plainspoken clarity. She sings honest stories about sorrow, longing, love, and the California landscape. Images surface like gold. (“I'm really a frustrated painter,” she said.) Hills turn brown, fruit hangs heavy on the vine. And in writing, perhaps more than any other device, images summon emotion.

When I listen to Kate Wolf, I hear my artistic true north.

“I don’t feel exposed,” she said. “What I sing about is really common to us all. It’s nothing secret.”

“People will say to me ‘Boy, you say just what I would say if I could figure out how to say it that way.’ And I've had that feeling about other people's work too, which is why sometimes I do other people's songs. Woody Guthrie has a great quote about this: ‘Let me be known as the person who told you what you already knew.' Sometimes we just can’t find the words [….] and then it comes and it’s just this breaking loose, you have a way to say it.”

Before I became a mom, I struggled with the turning point of Kate Wolf’s biography.

How I bristled at her leaving her family. I was parroting my own mother, of course. What the mom to my fourth grade classmate had done was beyond comprehension and against nature! How could she, my mom said about Mrs. T, and I once said about Kate Wolf.

The degree of my aversion should have told me something, but our own blind spots sometimes function like black holes.

“They say that you spend the first 35 years of your life reliving your parents’ lives,” Kate said in an interview when she was 43: “And then the years between 35 and 42 you kind of shake down. So I’d say the big shakedown happened and now it's starting to level out.”

Last month, a friend texted to hang out as I was driving out of town. I’ve abandoned my family for the night, I replied. I think she missed the “for the night” part. She was very concerned I was never going back. But my quarterly leavings are on the calendar; they are built into the rhythm of our family.

In Kate Wolf country for the night, I cried on the phone to a friend from a public park for such a prolonged period that finally, a cyclist approached. He was heading into a pizzeria, and did I want a slice?

That was kind, but no, thank you.

Tears are part of my “breaking loose.”

I ate a steak alone. I drank pink wine and read Trespasses and thought about the narrator, who was young and free (sort of). When I was young and free, I longed more than anything for love and a family.

I returned home the next afternoon, after a night in Kate Wolf country.

I’m in my big shakedown.

I write, mother, work, sing a bit. In the novel I’m writing, the male partner abandons the protagonist and their young child. The longer I sat with this plot point, the more I wondered if I had confused the protagonist’s fear of abandonment with her desire for freedom.

You know that Marianne Williamson quote? “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure.”

To make it plain: How could she is no longer a question I would ask.

“What gives love its most beautiful quality is the other side of it too. It’s a polarity,” Kate said:

“I really think that the blissed out state of love can get pretty boring. It’s like too much sugar. You have to have the dynamics of it so that it has its ups and downs, and highs and lows.”

The finest hour, that I have seen is the one that comes between the edge of night and the break of day, When the darkness rolls away.

For the next three albums, Kate moved out of the living room and into the studio. The Wildwood Flower had dissolved with her marriage, and in 1982 Kate married again, this time to Terry Fowler.

“He’d been kind of following me around for a couple of years. I didn’t know who he was, I just thought he was a real nice person. He got me out in the desert and was very quiet and sat me down and just started talking to me about what his feelings were. I was terrified. I didn’t want to have any more relationships. I said no, I can’t do this. And then I thought, well, there might be something here that just doesn’t look familiar, maybe you should sit down and look at it. So I ended up moving back here to Marin with him and six months later we got married. So that was almost four years ago.”

Her distributors launched a record label of their own and released Kate’s music to a wider audience. More magical things happened.

“The whole progression, which has excited me, is that the music has kind of made its own way. The songs go from people to people, people give each other the records, the records generate more records, and it sort of keeps going like that.”

It kept going like that beyond Northern California onto the national stage. Kate performed on “Austin City Limits” and “Prairie Home Companion.” She won Best Folk Record for 1983’s Give Yourself To Love, 1985’s Poet's Heart, and 1987’s Gold in California from the National Association of Independent Record Distributors and Manufacturers.

The thanks on each album tell a story:

Thanks to Max and Hannah Wolf — for helping Mom when things got busy

Special thanks: To my family for understanding.

Thanks: To Terry for sharing the dream and mastering the learn-as-you-go method of single parenthood while I was away.

In 1986, just as she was on the other side of the big shakedown, when she had “a real exciting feeling about this next decade,” Kate Wolf was diagnosed with acute leukemia.

“Give Blood for Kate” signs sprouted across Northern California at feed stores, head shops, food co-ops, bars, and colleges, in a grassroots campaign that expanded her fan base even further, right at the end. Now Kate Wolf was the recipient of benefits, with concerts performed nationwide to help defray her medical costs.2

“I’m tempted to say that Kate lives on in her music,” Berkeley’s KPFA dj Robbie Osman wrote on the liner notes to Kate’s posthumously released live record, Carry It On:

“But Kate knew that human lives begin and end and she understood that this knowledge is part of what makes our time profound and precious.”

Even the Kate Wolf Music Festival ends, which after 25 years, announced 2022 was the festival’s final year.

In 1985, an interviewer asked, Is there anything you especially live for or by in your life?

“Anything I especially live for or by? Well I would say that I live for a sense of a feeling of purposefulness in this world, you know, that I could stop my life at any point and feel that my life has been worthwhile, that the people I've loved and my children have all reached a point where their lives are now going to come to fruit. I feel that that’s real important. And that as far as something I live by it’s to try to be as alive as possible and feel free to make my mistakes and to be as honest as I can with myself which is always a process. Beyond that it all kind of blurs together. You get up in the morning and you feel like life is something that needs to be taken care of.”

Find what you really care about And live a life that shows it.

Chop wood, carry water. Write, mother, work, sing.

All biographical information in this piece, save for that footnote below, is from the treasure trove of articles and interviews on the Kate Wolf website, run by her family.

Gerald W. Haslam. Workin’ Man Blues: Country Music in California. University of California Press, 1999.