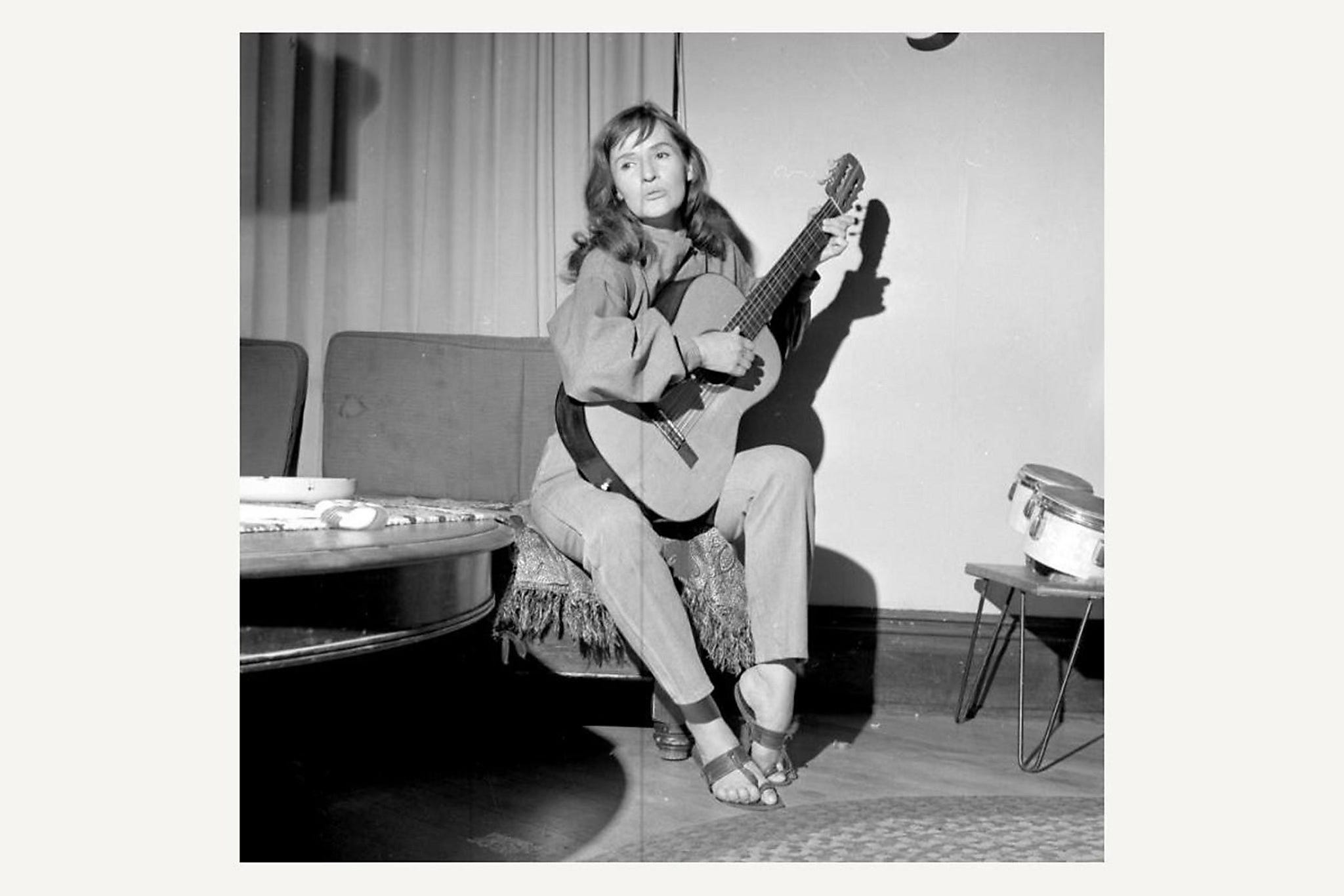

Rosalie Sorrels, Ford Econolines, folklore & family culture

“It took at least thirty-three years of my life for me to begin to try and find out who I am or what I am about. The awakening occurred through desperation." —Rosalie Sorrels

A babysitter brought a Rosalie Sorrels record over to Kate Wolf’s house. When I wrote about Kate, I said the record was “Rosalie Sorrels playing Utah Phillips.” That wasn’t quite true — half the songs were his and half the songs were hers — originals.

In Rosalie, Kate heard something that she could do, too; she sat right down to learn the entire album.

“It’s amazing the little things people drop in your way,” Wolf said.

I had never heard Rosalie Sorrels — at least, I didn’t think I had. One rainy night, driving home, I put on 1967’s If I Could Be the Rain — the record the babysitter brought to Kate’s house. I could scarcely believe how contemporary it sounded, the emotional freight of Angel Olsen meets Blossom Dearie’s jazz phrasings. In learning about Sorrels (pronounced Sor-RELS, like morels) I was introduced to Malvina Reynolds and Faith Petric, the matriarchs of a Bay Area folk tradition I like to envision as the West Coast mirror image of the communist, anti-war activism and literary legacy of Grace Paley set to guitar.

In 1985 — when Sorrels still had at least seven records ahead of her — music historian Elijah Wald called her a legend in the Boston Globe:

“She traveled around the country while raising five children. She drinks strong men under the table and is the first one up in the morning, bright and cheery and planning one of her famous dinners. And she can make the noisiest barroom crowd shut up and listen when she sings.”

Speaking of Sorrels to the Boston Globe in 2003, singer Christine Lavin said, “I think she’s influenced a lot of people who don’t even know her name.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LOST ART to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.